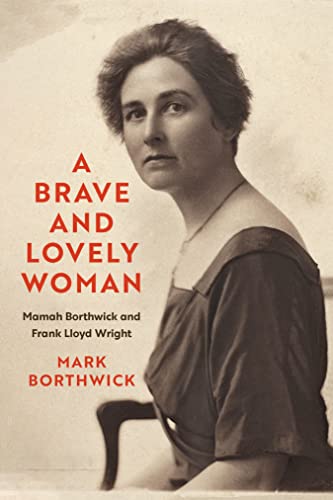

Book Review: 'A Brave and Lovely Woman'

In "A Brave and Lovely Woman," author Mark Borthwick examines the life and work of Mamah Borthwick—the woman often referred to in sensational terms as Frank Lloyd Wright’s “mistress"—revealing a serious scholar of language, of feminist thought and modern modes of living for men and women in early 20th-century America.

By Stuart Graff

Mamah (using her first name to distinguish her from the author, her distant cousin) has often been treated superficially by Wright’s biographers as merely the wife of a client, whom he whisked away to Europe in an extramarital affair that brought tragedy to the two of them. But Borthwick’s deep research, which uncovers extensive material not previously published, reveals a strong-willed and well-educated woman ambivalent about her own marriage and perhaps the institution of marriage itself—long before Wright comes into her life. Her work translating early feminist Ellen Key informs both Borthwick and Wright about different ways of thinking about marriage and relations between men and women in general, and as a result provides a guiding defense for their relationship. Borthwick’s account shows that Wright was far from being the womanizer he is often purported to be; rather, he sees Mamah as an equal and advocates for her as a professional and a scholar, with, as Borthwick notes, “a measure of respect that he did not always extend to others.”

Mamah (using her first name to distinguish her from the author, her distant cousin) has often been treated superficially by Wright’s biographers as merely the wife of a client, whom he whisked away to Europe in an extramarital affair that brought tragedy to the two of them. But Borthwick’s deep research, which uncovers extensive material not previously published, reveals a strong-willed and well-educated woman ambivalent about her own marriage and perhaps the institution of marriage itself—long before Wright comes into her life. Her work translating early feminist Ellen Key informs both Borthwick and Wright about different ways of thinking about marriage and relations between men and women in general, and as a result provides a guiding defense for their relationship. Borthwick’s account shows that Wright was far from being the womanizer he is often purported to be; rather, he sees Mamah as an equal and advocates for her as a professional and a scholar, with, as Borthwick notes, “a measure of respect that he did not always extend to others.”In this chronicle of Mamah’s and Wright’s struggles against the social mores of the day, two antagonists emerge. The “yellow press” of the day felt free to invent or exaggerate the details of their relationship, in a drive to sell newspapers and without regard to the personal impact on the lives of those involved in the affair; and these spurious accounts in turn have informed writers of fiction, plays and opera to present the matter through the lens of scandal. The other antagonist is Catherine Tobin, Wright’s wife, who refused for years to give him a divorce, who planted false information with the media, and who, it seems, manipulated her own children to embarrass Wright publicly. While sympathies may naturally extend to Catherine as a scorned spouse with young children, Borthwick makes it clear that much agony for all could have been avoided if she had given Wright the divorce he asked for, ending a marriage that was no longer working.

Borthwick also contributes new scholarship around the murder of Mamah and others at Taliesin. Where recent books have tried—and failed—to provide insight into the circumstances and motivations of the murderer, Borthwick triumphs with a fact-based narrative of the events that should definitively supplant the breathless speculation that has haunted the memory of August 1914. One hopes that this work finally deposes the fictional accounts of Mamah and Wright’s relationship with a richer, and truth-filled, story about two serious people trying to change the world around them for the better, finding support for and from each other.

Editor's note: Graff is the CEO of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

©2023, Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Used with permission.